The ancestor of fairy shrimp and relatives is found in fossils 500 million years old. Fairy shrimp branched off from this group 450 million years ago while they populated the ocean. But in the Devonian era, spanning 420 to 360 million years ago, the future of fairy shrimp was turned upside down. This was the age of the fishes, a time when fish diversified and dominated the ocean. The slow-moving, soft-body, defenseless fairy shrimp were easy prey for the now abundant fish. Eventually, fairy shrimp were gone forever from the ocean, but some had transitioned to fresh water and survived in remarkable ways. To this day, they only occupy freshwater habitats that are completely devoid of fish, like temporary ponds, shallow bodies of water that seasonally freeze solid, or bodies of water too salty for any fish. One local source of fairy shrimp is the vernal pool ecosystem of the Central Valley. Vernal pools contain water for a period of time long enough for fairy shrimp to survive and reproduce, but not so long that the pools support fish. Even a puddle of water that doesn’t drain may support fairy shrimp. A brine shrimp (essentially a fairy shrimp adapted to saline water) lives in hyper-saline water in the Bay Area. This is the San Francisco brine shrimp, which lives in the extremely briny, fishless salt ponds at the southern end of the bay. The ponds are noted for their vivid colors, especially from the air. The red colors come from the brine shrimp and microorganisms that thrive in the salty waters of the ponds.

If survival depends on living in a seasonal pool (because that’s how you avoid fish), how do you survive when the seasonal pond is dry, perhaps during a drought that lasts many years? Fairy shrimp have evolved a remarkable strategy. They survive dry periods as thick-walled eggs known as cysts. The embryonic shrimp inside the cyst goes into arrested development, a process called diapause. It’s a period of physiological dormancy that can last years, decades, or maybe centuries. No one is sure. The cysts remain in the dry pool bed until water of the appropriate temperature and quality becomes available. They then hatch and quickly mature into adults within days or weeks, depending on the species. The cysts of brine shrimp are sold in kits. In just days after water is added, the cysts hatch into swimming shrimp known as “Sea Monkeys.” The small animals are a novel source of entertainment. Cysts are unbelievably resilient. Brine shrimp cysts can survive boiling water for up to two hours, ultra-cold temperatures to -300 °F, prolonged desiccation, oxygen-free conditions, and trips into space! On Apollo 16 and 17, cysts went to the moon and back. Some cysts even survived periods of intense cosmic radiation.

Like many plants and animals in the California Floristic Province (much of California and slightly north and south of its borders), fairy shrimp are particularly well represented. In fact, California is considered a global diversity hotspot for fairy shrimp. The long hot and dry summers and short wet winters, typical of a Mediterranean climate, together with the right terrain, result in temporary pools that are not and could not be colonized by fish. Of the 26 species of fairy shrimp that call California home, 13 are found nowhere else. Other places in the world with a Mediterranean climate are similarly rich in fairy shrimp species. Fairy shrimp are typically filter feeders, actively swimming to scoop up algae and suspended microorganisms. In turn, fairy shrimp are eaten by many birds. Brine shrimp in salty lakes like the Great Salt Lake and Mono Lake are an important energy source for migrating phalaropes, avocets, grebes, and other birds. Elsewhere, flamingos often forage in saline lakes to feed on brine shrimp.

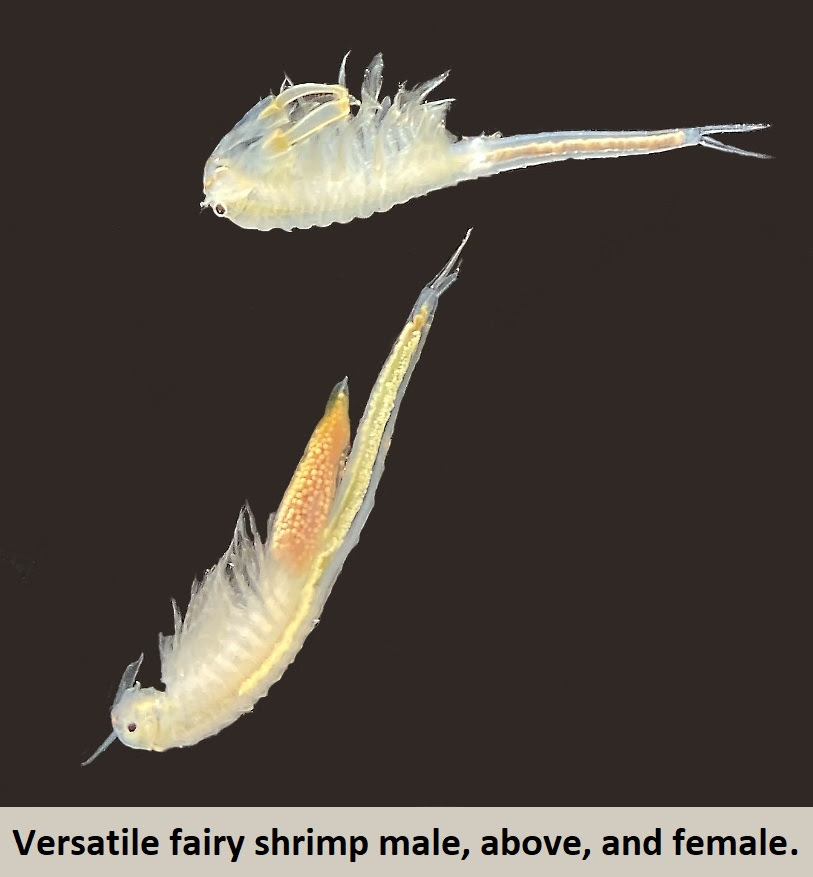

Fairy shrimp are recognized by their stalked compound eyes, upside-down swimming behavior, and modest size. Most are a little less than an inch long but the largest, the giant fairy shrimp, is up to three inches long. The giant fairy shrimp is an active predator of murky, saline waters of western Canada and the western U.S. It eats small crustaceans, including other fairy shrimp. Individual species of fairy shrimp and brine shrimp often are restricted to one location. The Mono Lake brine shrimp, for example, lives in the trillions in Mono Lake and nowhere else. It tolerates saline water more than twice as salty as the ocean. Species are still being discovered. Only two of the 26 fairy shrimp species in California were known prior to 1980, and eight were described after 1990. No doubt more will be found.

Vernal pool species expected in the Wildlife Area include the vernal pool fairy shrimp, conservancy fairy shrimp, midvalley fairy shrimp, the endangered vernal pool tadpole shrimp, and the California fairy shrimp, which has distinctive red eyes and is said to be the most common fairy shrimp in the Central Valley. The versatile fairy shrimp is also present in our area. The small mud puddle pictured here was home to at least two dozen. Tadpole shrimp are very close relatives of fairy shrimp. One is the longtail or rice paddy tadpole shrimp, which resembles a miniature horseshoe crab. They can negatively impact young rice fields when they stir up the bottom of the paddy, dislodging rice seedlings

Fairy shrimp lack dispersal mechanisms of their own. Cysts probably disperse in flood waters, in the wind, and inadvertently by waterfowl and other animals. Cysts pass through the digestive tracts of animals like the predatory diving beetle, which transports cysts to other places. Fairy shrimp and brine shrimp are found on all seven continents. There is even a species of fairy shrimp on mainland Antarctica.

At least 90% of vernal pool habitat once found throughout the Central Valley has been lost by land conversion. Today, there is fierce competition between conservation of vernal pools and development. Because vernal pools are a declining ecosystem in California, some fairy shrimp receive state or federal protection. Currently, four species in California are listed as endangered. As the public has become more educated about these amazing animals, interest in their conservation has grown. But fair warning. When fairy shrimp are on your radar, your worldview of mud puddles will be forever changed.

Photos: M. Davis